King James Version (1769) with Apocrypha & Tools

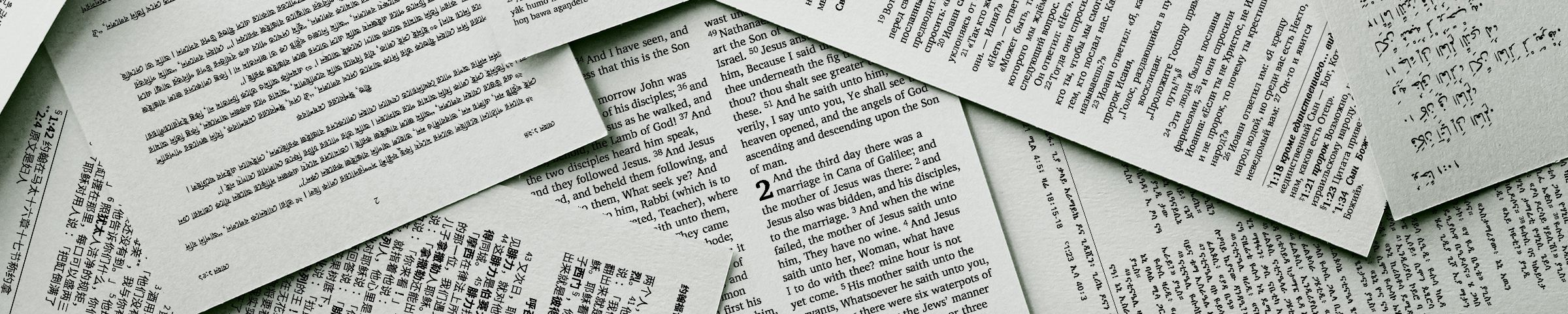

By the mid-18th century the wide variation in the various modernized printed texts of the Authorized Version, combined with the notorious accumulation of misprints, had reached the proportion of a scandal, and the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge both sought to produce an updated standard text. First of the two was the Cambridge edition of 1760, the culmination of 20 years' work by Francis Sawyer Parris, who died in May of that year. This 1760 edition was reprinted without change in 1762 and in John Baskerville's fine folio edition of 1763. This was effectively superseded by the 1769 Oxford edition, edited by Benjamin Blayney, though with comparatively few changes from Parris's edition; but which became the Oxford standard text, and is reproduced almost unchanged in most current printings. Parris and Blayney sought consistently to remove those elements of the 1611 and subsequent editions that they believed were due to the vagaries of printers, while incorporating most of the revised readings of the Cambridge editions of 1629 and 1638, and each also introducing a few improved readings of their own. They undertook the mammoth task of standardizing the wide variation in punctuation and spelling of the original, making many thousands of minor changes to the text. In addition, Blayney and Parris thoroughly revised and greatly extended the italicization of "supplied" words not found in the original languages by cross-checking against the presumed source texts. Blayney seems to have worked from the 1550 Stephanus edition of the Textus Receptus, rather than the later editions of Theodore Beza that the translators of the 1611 New Testament had favoured; accordingly the current Oxford standard text alters around a dozen italicizations where Beza and Stephanus differ. Like the 1611 edition, the 1769 Oxford edition included the Apocrypha, although Blayney tended to remove cross-references to the Books of the Apocrypha from the margins of their Old and New Testaments wherever these had been provided by the original translators. Altogether, the standardization of spelling and punctuation caused Blayney's 1769 text to differ from the 1611 text in around 24,000 places. Since that date, a few further changes have been introduced to the Oxford standard text. The Oxford University Press paperback edition of the "Authorized King James Version" provides Oxford's standard text, and also includes the prefatory section "The Translators to the Reader".

The 1611 and 1769 texts of the first three verses from I Corinthians 13 are given below.

[1611] 1. Though I speake with the tongues of men & of Angels, and haue not charity, I am become as sounding brasse or a tinkling cymbal. 2 And though I haue the gift of prophesie, and vnderstand all mysteries and all knowledge: and though I haue all faith, so that I could remooue mountaines, and haue no charitie, I am nothing. 3 And though I bestowe all my goods to feede the poore, and though I giue my body to bee burned, and haue not charitie, it profiteth me nothing.

[1769] 1. Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. 2 And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing. 3 And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing.

There are a number of superficial edits in these three verses: 11 changes of spelling, 16 changes of typesetting (including the changed conventions for the use of u and v), three changes of punctuation, and one variant text—where "not charity" is substituted for "no charity" in verse two, in the erroneous belief that the original reading was a misprint.

A particular verse for which Blayney's 1769 text differs from Parris's 1760 version is Matthew 5:13, where Parris (1760) has

Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt have lost his savour, wherewith shall it be salted? it is thenceforth good for nothing but to be cast out, and to be troden under foot of men.

Blayney (1769) changes 'lost his savour' to 'lost its savour', and troden to trodden.

For a period, Cambridge continued to issue Bibles using the Parris text, but the market demand for absolute standardization was now such that they eventually adapted Blayney's work but omitted some of the idiosyncratic Oxford spellings. By the mid-19th century, almost all printings of the Authorized Version were derived from the 1769 Oxford text—increasingly without Blayney's variant notes and cross references, and commonly excluding the Apocrypha. One exception to this was a scrupulous original-spelling, page-for-page, and line-for-line reprint of the 1611 edition (including all chapter headings, marginalia, and original italicization, but with Roman type substituted for the black letter of the original), published by Oxford in 1833. Another important exception was the 1873 Cambridge Paragraph Bible, thoroughly revised, modernized and re-edited by F. H. A. Scrivener, who for the first time consistently identified the source texts underlying the 1611 translation and its marginal notes. Scrivener, like Blayney, opted to revise the translation where he considered the judgement of the 1611 translators had been faulty. In 2005, Cambridge University Press released its New Cambridge Paragraph Bible with Apocrypha, edited by David Norton, which followed in the spirit of Scrivener's work, attempting to bring spelling to present-day standards. Norton also innovated with the introduction of quotation marks, while returning to a hypothetical 1611 text, so far as possible, to the wording used by its translators, especially in the light of the re-emphasis on some of their draft documents. This text has been issued in paperback by Penguin Books.

From the early 19th century the Authorized Version has remained almost completely unchanged—and since, due to advances in printing technology, it could now be produced in very large editions for mass sale, it established complete dominance in public and ecclesiastical use in the English-speaking Protestant world. Academic debate through that century, however, increasingly reflected concerns about the Authorized Version shared by some scholars: (a) that subsequent study in oriental languages suggested a need to revise the translation of the Hebrew Bible—both in terms of specific vocabulary, and also in distinguishing descriptive terms from proper names; (b) that the Authorized Version was unsatisfactory in translating the same Greek words and phrases into different English, especially where parallel passages are found in the synoptic gospels; and (c) in the light of subsequent ancient manuscript discoveries, the New Testament translation base of the Greek Textus Receptus could no longer be considered to be the best representation of the original text.

Responding to these concerns, the Convocation of Canterbury resolved in 1870 to undertake a revision of the text of the Authorized Version, intending to retain the original text "except where in the judgement of competent scholars such a change is necessary". The resulting revision was issued as the Revised Version in 1881 (New Testament), 1885 (Old Testament) and 1894 (Apocrypha); but, although it sold widely, the revision did not find popular favour, and it was only reluctantly in 1899 that Convocation approved it for reading in churches.

By the early 20th century, editing had been completed in Cambridge's text, with at least 6 new changes since 1769, and the reversing of at least 30 of the standard Oxford readings. The distinct Cambridge text was printed in the millions, and after the Second World War "the unchanging steadiness of the KJB was a huge asset." The Cambridge edition is preferred by scholars.

The Authorized Version maintained its effective dominance throughout the first half of the 20th century. New translations in the second half of the 20th century displaced its 250 years of dominance (roughly 1700 to 1950), but groups do exist—sometimes termed the King James Only movement—that distrust anything not in agreement with the Authorized Version. (Wikipedia)

The 1611 and 1769 texts of the first three verses from I Corinthians 13 are given below.

[1611] 1. Though I speake with the tongues of men & of Angels, and haue not charity, I am become as sounding brasse or a tinkling cymbal. 2 And though I haue the gift of prophesie, and vnderstand all mysteries and all knowledge: and though I haue all faith, so that I could remooue mountaines, and haue no charitie, I am nothing. 3 And though I bestowe all my goods to feede the poore, and though I giue my body to bee burned, and haue not charitie, it profiteth me nothing.

[1769] 1. Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. 2 And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing. 3 And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing.

There are a number of superficial edits in these three verses: 11 changes of spelling, 16 changes of typesetting (including the changed conventions for the use of u and v), three changes of punctuation, and one variant text—where "not charity" is substituted for "no charity" in verse two, in the erroneous belief that the original reading was a misprint.

A particular verse for which Blayney's 1769 text differs from Parris's 1760 version is Matthew 5:13, where Parris (1760) has

Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt have lost his savour, wherewith shall it be salted? it is thenceforth good for nothing but to be cast out, and to be troden under foot of men.

Blayney (1769) changes 'lost his savour' to 'lost its savour', and troden to trodden.

For a period, Cambridge continued to issue Bibles using the Parris text, but the market demand for absolute standardization was now such that they eventually adapted Blayney's work but omitted some of the idiosyncratic Oxford spellings. By the mid-19th century, almost all printings of the Authorized Version were derived from the 1769 Oxford text—increasingly without Blayney's variant notes and cross references, and commonly excluding the Apocrypha. One exception to this was a scrupulous original-spelling, page-for-page, and line-for-line reprint of the 1611 edition (including all chapter headings, marginalia, and original italicization, but with Roman type substituted for the black letter of the original), published by Oxford in 1833. Another important exception was the 1873 Cambridge Paragraph Bible, thoroughly revised, modernized and re-edited by F. H. A. Scrivener, who for the first time consistently identified the source texts underlying the 1611 translation and its marginal notes. Scrivener, like Blayney, opted to revise the translation where he considered the judgement of the 1611 translators had been faulty. In 2005, Cambridge University Press released its New Cambridge Paragraph Bible with Apocrypha, edited by David Norton, which followed in the spirit of Scrivener's work, attempting to bring spelling to present-day standards. Norton also innovated with the introduction of quotation marks, while returning to a hypothetical 1611 text, so far as possible, to the wording used by its translators, especially in the light of the re-emphasis on some of their draft documents. This text has been issued in paperback by Penguin Books.

From the early 19th century the Authorized Version has remained almost completely unchanged—and since, due to advances in printing technology, it could now be produced in very large editions for mass sale, it established complete dominance in public and ecclesiastical use in the English-speaking Protestant world. Academic debate through that century, however, increasingly reflected concerns about the Authorized Version shared by some scholars: (a) that subsequent study in oriental languages suggested a need to revise the translation of the Hebrew Bible—both in terms of specific vocabulary, and also in distinguishing descriptive terms from proper names; (b) that the Authorized Version was unsatisfactory in translating the same Greek words and phrases into different English, especially where parallel passages are found in the synoptic gospels; and (c) in the light of subsequent ancient manuscript discoveries, the New Testament translation base of the Greek Textus Receptus could no longer be considered to be the best representation of the original text.

Responding to these concerns, the Convocation of Canterbury resolved in 1870 to undertake a revision of the text of the Authorized Version, intending to retain the original text "except where in the judgement of competent scholars such a change is necessary". The resulting revision was issued as the Revised Version in 1881 (New Testament), 1885 (Old Testament) and 1894 (Apocrypha); but, although it sold widely, the revision did not find popular favour, and it was only reluctantly in 1899 that Convocation approved it for reading in churches.

By the early 20th century, editing had been completed in Cambridge's text, with at least 6 new changes since 1769, and the reversing of at least 30 of the standard Oxford readings. The distinct Cambridge text was printed in the millions, and after the Second World War "the unchanging steadiness of the KJB was a huge asset." The Cambridge edition is preferred by scholars.

The Authorized Version maintained its effective dominance throughout the first half of the 20th century. New translations in the second half of the 20th century displaced its 250 years of dominance (roughly 1700 to 1950), but groups do exist—sometimes termed the King James Only movement—that distrust anything not in agreement with the Authorized Version. (Wikipedia)

Language English [eng]

Date 1769

Copyright Public Domain OPEN

Historic Bible Scans

The Bible Archive